Principles & Processes

Building a Ladder of Engagement for Youth

Young people bring critical perspective, expertise, and energy to our movement spaces -- but traditional organizing and mobilizing structures can leave them feeling undervalued, tokenized, or burnt out.

How do we design ladders of engagement that truly support youth leadership development within our climate organizing work?

Participants will leave this Lab training with:

• Evidence-insights into the challenges and opportunities of youth climate organizing

Info session for the Blueprint for MRXC Climate Coalitions training series

The Lab is planning a four-part training series based on our Blueprint for MRXC Climate Coalitions project. Our goal is to help the Lab community develop more durable, effective, and equitable coalitions to win the climate solutions we need. This series is open to advocates who want help setting up a coalition, are currently working in coalition, or just want to learn best-practices for their next coalition. Come to this info session to learn more about the timeline, scope, and design principles for this all-new training series!

Series breakdown:

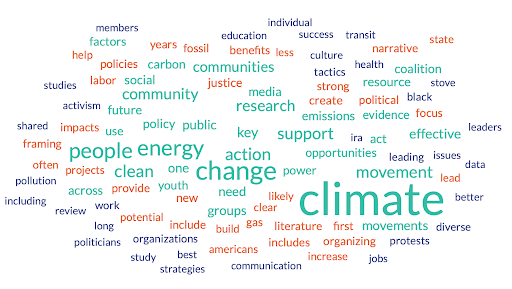

Notable research of 2023

Inflation Reduction Act

Replenishing trust: Civil society’s guide to reversing the trust deficit

Trust-building is actions aligned to values — it’s not just communicating about what matters, but doing it. Trust for institutions across society is declining. This growing trust deficit is a serious problem: It erodes a high-functioning pluralistic democracy, compromises public health and makes it impossible to solve collective problems like climate change. Trust doesn’t just happen. American civil society institutions have an important role to play in increasing trust — which is necessary to create the kind of world we all want to live in.

The Momentum Model: A Living Model for Hybrid Organizing

Launch Event: Blueprint for a Multiracial, Cross-Class Climate Movement

The Kernel: A Tool for Developing Good Strategy (and Avoiding Bad Strategy)

Blueprint for a Multiracial, Cross-Class Climate Movement: The Workbook for Coalitions

This workbook is meant to help you translate the analysis and recommendations we provide there into workable features of your organizing. Whether you’re currently involved in a multiracial, cross-class climate coalition, thinking about starting one, or evaluating a past coalition on reflection, we hope this workbook clarifies for you and your coalition partners the breadth of considerations and decisions you should be prepared for.

Blueprint for a Multiracial, Cross-Class Climate Movement: The Report on Coalitions

Multiracial, cross-class (MRXC) coalition-building is essential if the climate movement is serious about tackling the climate crisis at the scale it demands. However, a historical lack of collaboration, trust, or healthy mechanisms to deal with conflict often impair those efforts. This Blueprint report and accompanying workbook provide an analysis of the difficulties MRXC climate coalitions are likely to face and offer recommendations for a proposed path forward.

Pagination

- Page 1

- Next page